Some heart-wrenching patient stories...

...and the story of another patient that actually made many folk's blood boil...

The story of one donor...

"Lori Beattie, 22, who is waiting for a second lung transplant, has been in intensive care since last July, the longest stay for any of the current patients." - from a June 15, 1998 article about Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (photo by Andy Starnes). She had spent 11 months in intensive care at the time of the article. Can you imagine living for 11 months in an intensive care ward? Apparently our congressmen either aren't troubled by her dilemma, or are simply ignorant of basic economics. (Whenever the supply of any market commodity is low, a price rise is the incentive that spurs increased supply. If prices are capped artificially at zero, there can be no monetary incentive for the supply to increase. Altruistic motives alone have proven to be woefully inadequate.)

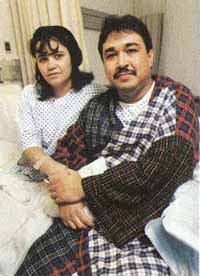

Maria Lugo had to sacrifice one of her own kidneys to save the life of her husband Jorge.

If the U.S. Congress had not prohibited Organ Procurement Organizations

from offering monetary thank-you gifts for cadaveric human organ donation, a suitable cadaveric

organ likely would have been available, and she might not have had to risk her life and

undergo the trauma of surgery. They are shown here, soon after their joint

operation. Jorge was back at work a mere 5 weeks after surgery, while Maria had to

wait 10 weeks.

Dominic, a 4 year old boy (as of early 2000) with end-stage renal disease, stands next to

his (Baxter Homechoice) dialysis machine. How long will he have to wait for a donor

kidney? There'd be no wait if a free market in cadaveric organs were allowed to

develop. In fact, there might then be too many

organs, if that makes any sense.

From the [currently defunct, but functioning as of early 2000] DelCimmuto family website: "Our

daughter Jessica DelCimmuto waited for 4 months for organs but unfortunately her fragile

condition could not hold out any longer. On February 9th, 1998 Jessica passed

away." [The tube stretching under her nose supplied her with oxygen.]

Man still waits for liver after six years

by Joe Carmody, Staff Writer (from The Pitt News,

December 12, 1999)

When he entered through the brass and oak doors of John Harvard's

Brew House, David Somerville appeared to be far from his

marathon running days. After wiping his feet, he walked toward the bar and made a

valiant effort to shake off December's chills. His expression remained neutral -

neither calm nor anxious. He spoke slowly.

"I'm tired," said Somerville, who has been waiting for a

liver transplant since 1993.

The Latrobe, Pa., resident's wait for a liver began in the spring of

1993 while he was preparing for a race. While running, Somerville said he felt

strange and noted sensations he hadn't felt during an event in Erie the previous year.

He returned home and told his wife, Kathy, who promptly informed her

husband that he was getting old.

"I told him we're all in the same boat as the years go on,"

she said.

"I didn't know what it was," David Somerville said.

"I didn't feel good. I had a real, real good day training, and then the next

day, I was exhausted."

In June, he visited the Latrobe Area Hospital for a physical and some

blood work. It was then that doctors discovered some signs of elevated enzymes from

his liver. Taking their advice, Somerville underwent a CT scan so doctors could

examine the soft tissues of his body.

Somerville, a family man who enjoys traveling, decided to vacation at

Myrtle Beach before hearing the news that he would have to undergo androscopic surgery on

Aug. 31, his 45th birthday.

"I actually reported to work in the morning and left to go to the

11 o'clock procedure. I've never been back since," Somerville said.

The doctors found that Somerville's common bile, a thick alkaline fluid

that is secreted by the liver and stored in the gallbladder, had almost totally clogged

his bile ducts. Doctors said he had cancer and gave Somerville six to eight months

to live.

"I was shocked and in a state of denial," Kathy Somerville

said.

But a urologist in Latrobe thought it might be something else, and

after a few more hospital visits, David Somerville was transferred to the University of

Pittsburgh Medical Center in search of a liver transplant.

"It was like one emotional turn into another. Although there

was still a ways to go, it was like Christmas to find out it wasn't cancer," Kathy

Somerville said.

David Somerville suffers from primary sclerosing cholangitis, a disease

that begins when the bile ducts become blocked and cause the liver to become inflamed and

scarred. This is the same disease that killed Chicago Bears running back Walter

Payton.

Somerville is listed as a Status 3 patient at UPMC. This means he

is under medical care but is only occasionally in the hospital. A Status 2 patient's

condition is more serious, and he or she is closer to receiving a transplant. At

Status 1, a patient is under intensive care with only hours or days to live or, as

Somerville put it, 'As a Status 1, life is precious."

"Overall, when I first enrolled on the waiting list, I think there

were 35 [thousand] people [, nationally,] waiting for all types of organs. Today,

there are 1,600 hopefuls in this region," Somerville said. "I've been a

Status 3 since '93. My disease is chronic, and that might have something to do with

the consistence, but I'd never want to be a Status 1."

The problem for Americans awaiting transplants is that there's a severe

shortage of organs. An estimated 61,000 people are waiting for hearts, lungs,

livers, kidneys and pancreases, and the demand far exceeds the supply. According to

government reports, about 4,000 people die each year while waiting for donated organs -

that's roughly 11 people each day.

"The answer to this problem is for more people to become

donors," Somerville said. "The reason people don't is because the need for

a transplant hasn't affected them yet."

Somerville believes that although more than 60,000 patients - enough to

fill Three Rivers Stadium - are waiting there are probably 1 million family members and

friends also waiting. "While I wait, others wait with me," said

Somerville, who recently participated in a hearing on organ donation in Pittsburgh,

attended by U.S. Senators Arlen Specter and Rick Santorum of Pennsylvania.

"We go through things together," Kathy Somerville said.

Under the current system, donated organs are given to patients at

transplant centers near the donors. Priority is not given to sicker patients outside

the hospital's region. U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Donna Shalala has

issued a proposal to create a more widespread allocation system that would give organs to

the sickest patients without regard to their locations, but Congress has delayed voting on

the rule change.

Somerville, 51, isn't sure if a wider sharing system would help his

cause. "By its own nature, it's supposed to help the sickest people first, and

I don't fall into that category. But I think ethically it's the right way to

go," he said.

Realistically, the current system doesn't favor Somerville.

Although he has spent the past six years waiting for a liver, the new regulations do not

consider waiting time as part of the transplant criteria because his case isn't critical

when compared to Status 1 patients.

Referring to the United Network for Organ Sharing, Somerville said,

"I thought 'united' means togetherness, but those in charge are all pulling for

themselves."

So how does this man find hope and continue in his role as husband,

father and citizen after enduring such a dramatic wake-up call? "You have to

find a reason to get up in the morning even when you're not feeling good," he said.

"There's a reversal of roles. I do a lot of stuff around the

house, and Kathy goes out and teaches. I try to take the stress off of her. We

joke about it, but I make her breakfast every day and warm up the car," Somerville

added.

Since retiring from the insurance business when he enrolled on UPMC's

waiting list, Somerville has remained busy through a variety of groups and associations.

He has resumed a leadership position with the Westmoreland-Fayette Council Boy

Scouts, which brought his to Western Pennsylvania after he and his wife graduated from

Lock Haven University in 1971. Somerville works in the Boy Scouts' marketing

division and prepares press releases and articles for their newsletter.

He has become an active member of the personnel committee at Latrobe's

United Methodist Church. The church also serves as a meeting place for a Greensburg

support group for people awaiting organs, in which Somerville participates.

"We don't have a regular program - no officers - and it sometimes

turns into a gripe session," he said. "But I'm starting to learn a lot

from everybody. There are some things I didn't know about that I do now."

In the past year, three Status 1 patients have attended meetings of the

Greensburg group. One died, another received a heart transplant after waiting 9½

months, and another received a double lung transplant. Both survivors are doing very

well. "So we've seen two successes and one failure - not too bad,"

Somerville said. [NOTE: in a subsequent private conversation with this website author,

David wished to retract that statement, saying "even one death is one too

many."]

Somerville also speaks at local high schools on behalf of the Center

for Organ Recovery and Education to explain and clarify the importance of organ donations.

CORE is a nonprofit organization that plays a significant role in the relationship

between the families of donors and the patients receiving their organs. The office

in Pittsburgh serves 5.7 million people throughout southern New York, central and western

Pennsylvania, and West Virginia.

"We've found that 39 percent of all donors are either in high

school or college. It's my generation, the baby boomers, who need to do more,"

Somerville said.

The group is thankful for research centers such as UPMC and the

Cleveland Clinic for their progress in the transplant field. "Perhaps down the

road, they can take one of my liver cells and grow it into a big liver and transplant it

into myself. That way it eliminates rejection and the donor process. That's a

neat concept - that's what could happen. I wish it would happen tomorrow,"

Somerville said with a smile.

Somerville believes he is fortunate because of his proximity to UPMC.

During his hospital visits over the years, he's become acquainted with people from

all over the country. "I was staying at the patient center on Craig Street, and

I met a fellow from Maine. I said, 'What are you doing in Pittsburgh? Isn't

there a center in Massachusetts?' He said, 'I came here because this place is the

best,'" Somerville related.

Although Somerville says the waiting process is wearing him down, as

well as his family and friends, he maintains optimism by planning weekend getaways and

praying for a less turbulent path ahead.

"When David gets ill, I'm thinking, 'Could this be it?'"

Kathy Somerville said. "So we live life while we can and experience it, not

just sit back."

"I guess life is what you make of it," David Somerville said.

And, while such patients wait desperately for donor organs, our congressmen piously refuse to consider lifting their ban on the sale or purchase of human organs, resulting in the deadly shortage.