Legislation and Legislative History

- The original, National Organ Transplant Act of 1984 (public law 98-507, i.e., 98th Congress, 507th law passed)

- excerpts from accompanying U.S. Senate report

- list of U.S. Senate sponsors of the 1984 legislation

- list of U.S. House sponsors of the 1984 legislation

- U.S. House testimony in favor of the ban

- U.S. House testimony in opposition to the ban

- Pennsylvania's proposed organ-donor funeral reimbursement plan

Scientific Articles

- Journal of Transplant Coordination (1999):"Willingness to donate organs and tissues in Vietnam", by Tran Bac Hai et al.

- Issues in Medical Ethics (IX(2): 44-46, April-June, 2001): "The Ethics of Organ Selling: A Libertarian Perspective", by Harold Kyriazi [yours truly]

- Journal of Medical Ethics (27: 30-35, Feb. 2001): "Shifting ethics: debating the incentive question in organ transplantation", by Donald Joralemon [Editor's note: this article, available on-line, provides a reasonably unbiased analysis of the debate, and has tons of good references, both pro and con]

Press Articles

- David Rothman's "The International Organ Traffic"

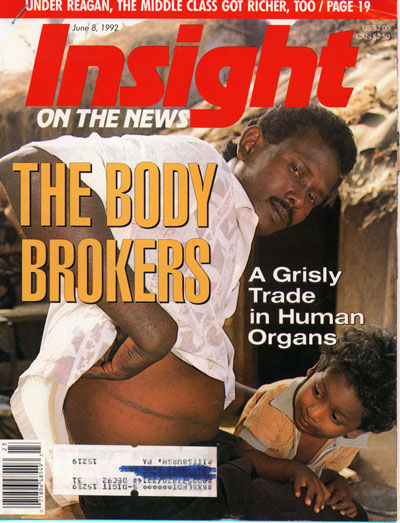

- Insight magazine's 1992 cover story, "The Organ Brokers"

- "Transplanting Life: The

Triumphs, The Traps, The Tragedies."

A Five-Part Series by The Plain Dealer - San Diego Union-Tribune article about one donor and her many recipients, "Of death and life"

- Dear Abby column

- CATO Institute column (this is on an adjacent page)

- AMA reconsidering the ban on selling (at June, 2002 meeting)

- AMA recommends experimenting with monetary incentives (June 2002)

- UCLA law professor recommends monetary incentives for cadaveric donation (October 30, 2005)

ABC News' 20/20, John

Stossel report, "Organs for Sale? With So Many People in Need

of Organs, Why Can't They Buy Them?" (August 8, 2003)

CBS News'

48 Hours Special ("Your Money or Your Life" -- first aired

Monday, Feb. 11, 2002)

An Inspirational Poem (from the mother of a donor)

"Willingness to donate organs and tissues in Vietnam" by Tran Bac Hai, Ted Eastlund, MD, Le Anh Chien, Phan Thi Hong Duc, Tran Huong Giang, Nguyen Thi Nguyen Hoa, Phan Hong Viet, and Duong Quang Trung, MD, Journal of Transplant Coordination 9(1): 57-63 (1999). The following quote is from p. 62: "We observed that many families preferred to receive monetary or other material inducements for donating organs or tissues from deceased family members." [Straight from the horse's mouth! And why shouldn't they receive some compensation, as a small token of gratitude?]

David Rothman's New York Review of Books article, "The

International Organ Traffic" (The New York Review, March 26, 1998)

"The market in organs has its

defenders. To refuse the sellers a chance to make the money they need, it is said, would

be an unjustifiable form of paternalism. Moreover, the sellers may not be at greater risk

living with one kidney, at least according to US research. A University of Minnesota

transplant team compared seventy-eight kidney donors with their siblings twenty years or

more after the surgery took place, and found no significant differences between them in

health; indeed, risk-conscious insurance companies do not raise their rates for kidney

donors. And why ban the sale of kidneys when the sale of other body parts, including

semen, female eggs, hair, and blood, is allowed in many countries? The argument that these

are renewable body parts is not persuasive if life without a kidney does not compromise

health. Finally, transplant surgeons, nurses, and social workers, as well as transplant

retrieval teams and the hospitals, are all paid for their work. Why should only

the donor and the donor's family go without compensation?"

From the 1998

David Rothman, NY Review article. Note the long abdominal scar. (It looks a bit like she

has a rope around her waist.)

From the 1998

David Rothman, NY Review article. Note the long abdominal scar. (It looks a bit like she

has a rope around her waist.)

June 8, 1992 Insight magazine cover story.

Body Shops, by Stephen Brookes

Squatting in a dirt alley in the Indian slum of Villivakkam, the slight

young man pulls up his shirt and runs his finger along the rough, 8-inch scar that erupts

below his rib cage and runs down his abdomen into the folds of his skirt-like lunghi.

"This is where they cut me open to get the kidney out," he murmurs,

describing the operation he underwent in a Madras hospital three years ago.

"They paid me 20,000 rupees (about $800) for it, half before and half after.

It's all gone now," he says, laughing self-consciously. "I had a lot of

debts, and I drank the rest. I was stupid, and now I'm sick. I can't even work

anymore. I'm 27 years old, and if I carry a bucket of water down the street I have

to sit down and rest."

It's a story that's becoming increasingly familiar across India, Latin

America and other parts of the developing world: poor people recruited from slums and

shantytowns to sell parts of their bodies for quick cash. The buyers: wealthy

Japanese, Middle Easterners and Europeans who, frustrated with laws against buying organs

in their home countries, go abroad to countries where they can check into a hospital, find

a middleman to procure a donor, pay for the transplant and return home - all in a matter

of weeks. "The practice is apparently widespread, from what we've been

hearing," says an official with the World Health Organization in Geneva.

"And we're very concerned."

The concern is warranted. With kidneys selling for anywhere from

a few hundred to tens of thousands of dollars, the trade has become so lucrative that

there have been reports - some substantiated, some questionable - of children in Argentina

being stolen and killed for their organs, of Chinese prisoners executed and their kidneys

sold, of prisoners in the Philippines being released after donating a kidney, of bodies

washing up on Brazilian beaches with their organs surgically removed. At one

psychiatric clinic outside of Buenos Aires, Argentina, doctors have been accused of

murdering lunatics for their body parts. Large, well-organized trafficking rings

have even been uncovered: in December, Juan Andres Ramirez, Interior Minister of Uruguay,

announced the arrest of 20 persons who were allegedly flying slum dwellers to other

countries to "donate" their organs.

While some of the stories are patently untrue - widespread reports in

the early 1980s that Latin American children were being stolen and their organs sold to

rich Westerners, for example, were later shown to be part of a bizarre Soviet

disinformation campaign - there are thriving, well-documented and quite legal markets in

Bombay, Madras and Calcutta in India, and in Manila, Cairo and Hong Kong. Many of

the buyers are nationals, but much of the trade is fueled with oil money from outside.

"Most of the buyers are coming from the Emirates, Qatar and Kuwait," says

the World Health Organization official, describing the kidney business in Cairo and

Bombay. "Apparently there's a big shortage of kidneys in the Gulf states right

now, because of the war."

The growth of this grisly trade has resulted from two related trends

over the past two decades. On the one hand, medical and technological developments

have raised the success rate of transplants and increased the demand for organs; but as

demand has gone up, laws have been implemented in most of the world forbidding people to

pay organ donors, thus cutting down the potential supply. That imbalance has spawned

a complex network of desperate buyers, shady middlemen, opportunistic doctors, and poor

and uneducated donors.

While corneas, lungs and other organs can be transplanted from live

donors, most of the trade is in kidneys, since a healthy, well-nourished donor can live

reasonably well with only one. Since the first renal transplant was done in 1954

between twin brothers, the survival rate has gone up dramatically, thanks to advances in

surgical techniques, the training of large numbers of transplant surgeons and the

development of drugs such as cyclosporine that suppress immune system attacks on

transplanted organs. For patients who suffer from chronic kidney failure, there is

now greater hope that they can be released from the expensive, endless and intrusive

mechanical process of dialysis (which cleanses impurities from the blood) and live a

normal life with a transplant.

But finding a donor is not easy. Successful transplants rely on a

good blood and tissue match between donor and recipient, and the best donors are often

members of one's family. But patients who lack a willing family member have only two

choices: wait until a properly matched kidney from a cadaver becomes available or go to

one of the world's kidney marketplaces.

Until a few years ago it was possible in the United States and Europe

to bring donors in from outside. As early as 1985, the World Medical Association

noted that "in the recent past a trade of considerable financial gain has developed

with live kidneys from underdeveloped countries for transplantation in Europe and the

United States."

But as more and more such cases came to light, governments began to

respond. Washington outlawed trade in body parts with the National Organ Transplant

Act of 1984 - sparked by the revelation that a doctor in Virginia had circulated brochures

in the Caribbean, offering people a free two-week vacation in the United States if they

agreed to leave a kidney behind when they went home.

Other Western governments soon followed suit.

... In one notorious 1988 case, a German company called the Association

of Organ Donations and Mutual Human Substitution sifted through public bankruptcy notices

to find prospective clients, then sent them a letter that read, "You're broke.

You're a social leper, tainted with the legal and social equivalent of AIDS. The

most horrid vultures will pursue you. ...In case you don't have the guts for a life of

crime, if your courage isn't up to a big break-in, a bank heist or a new life abroad, I

offer you a solution founded on logic. Donate your kidney."

The founder of the company, Count Rainer Rene Adelmann von

Adelmannsfelden, offered to pay up to $45,000 for kidneys and to arrange operations -

including doctor, donor and hospital fees - for $85,000, taking a 10% cut for himself. ...

Nor is Asia spared. Japanese suffering from kidney disorders

are said to flock to Manila for transplants, while wealthy residents of Hong Kong and

Singapore reportedly cross the Hong Kong border into Guangzhou in southern China.

According to Hong Kong doctors and human rights groups, an organization

calling itself the Kidney Transplant Service Center has offered package tours to China for

kidney transplants, and a prominent Hong Kong doctor told the British medical journal

Lancet recently that customers pay about $20,000 for a kidney transplant.

But there have also been more sinister

reports of transplants done at Nanfang Hospital in Guangzhou, in which prisoners

were executed and their organs removed for sale to foreigners (at a going

rate of $10,000 to $13,000) or high Chinese officials. The details were confirmed

by a Chinese police official, who told the International League for Human Rights that

"those who were executed would have their organs removed for transplant without prior

consent or that of their families. For example, a colleague of mine who was going

blind took the eyes of a prisoner who was executed. In order to

preserve the eyes, the prisoner was shot in the heart rather than in the head. This

is what happens. If they need the heart, the prisoner would be shot in the head

instead."

When asked who would actually remove the organs, the police official

said a doctor and a nurse would arrive in an ambulance. "Immediately after the

execution, the coroner would examine the corpse and certify the death. The corpse

would then be taken immediately inside the ambulance, where the necessary organs are

removed. The corpse is then taken out of the ambulance and returned to the family.

No one has seen the doctor or nurse, and no one is aware of the reason why they

were there."

While the trade thrives in China, Hong Kong and the Philippines, it is

also strong in the Middle East. ...

While a poor man can make a few thousand dollars, it's the middlemen -

the people who bring foreign buyers and sellers together - who really profit. One

such middleman, who agreed to talk anonymously about his business, met with

Insight late one night on a side street on the outskirts of Cairo. A

smooth-talking operator, fluent in English, French and Italian as well as his native

Arabic, he wore expensive European clothes, chain-smoked Gauloise cigarettes and sat in

the backseat of a gold Mercedes as he described some of the kidney transplants he had

arranged. "It's very simple, and it happens all the time," he says.

"The first one was in 1987. I was working at the Sheraton el-Gezira, and there

was a guest staying there, a Kuwaiti. He'd been asking around about finding someone

who would sell their kidney, and I went up to see him. He was about 30. He

said he'd made arrangements for the operation, but had to find a donor. And he said

he'd pay $9,000.

"So I got in touch with my brother, who's a soldier in the Seqoa

Oasis. He had a houseboy there, a Bedouin. He was about 20, I think. He

agreed to come up to Cairo, they did the blood tests, and they did the operation a few

days later." In all, he says, there were six persons involved: the seller, the

donor, himself, the doctor and a couple of nurses. "The Kuwaiti paid $29,000

for everything. I got $7,000. The Bedouin got $2,000, and the rest went to the

doctors and the nurses. The Kuwaiti went back home, and about six months later I got

a call from a friend of his, another guy who needed a kidney. It's a good

business," he says, sitting back in the Mercedes and smiling.

If business is good in Egypt, it's even better in India. ...

Supply & Demand [sidebar]

As the demand for kidneys shoots up, is there any way to increase the

supply without legalizing a live donor market? In the United States and other

developed countries, the technology exists to remove kidneys from cadavers, freeze them,

match them to a potential recipient through a centralized directory and then quickly

deliver them. Under the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act, people can authorize the

postmortem donation of their organs, and in most states people can indicate on their

driver's licenses if they are willing to let their organs be removed for transplanting.

Yet in spite of encouragement from doctors, the government and some

religious leaders, many people simply refuse. There are some 15,000 to 25,000 deaths

of healthy people in the United States every year, but only about 20 percent of those

result in donations, leaving the supply far short of the 13,000 to 15,000 kidneys needed

every year.

"The harsh reality is that, with respect to cadaver donation,

you're never going to get enough to meet demand," says Arthur L. Caplan, a medical

ethicist at the University of Minnesota.

Caplan and others believe that while the debate on allowing people to

sell their organs may heat up in the future, there are so many complex practical and

ethical issues involved that the laws are unlikely to change.

The organ shortages of the future will probably be met by other means,

they say: Xenografting - or transplanting animal organs into humans - remains a promising

solution, and the use of mechanical devices to replace certain organs is also developing.

And as biotechnology develops, it may eventually be possible to grow

whole organs from a few cells - making test tubes the organ donors of the future. [end

sidebar]

[The article is long, and continues to document the horrors of the trade. I can't help but note the similarity between this and the trade in illegal, recreational drugs, where the government "solution" is a hundred times worse than the perceived problem. Reagan was largely correct when he said, "Government isn't the solution. Government is the problem."]

Dear Abby

by Abigail Van Buren

From the San Diego Union-Tribune, Sunday, January 23, 2000

[Responding to a tax attorney who wrote, "I am not in support of the person who suggests that we give incentives to encourage people to become organ donors. The incentive should be that you are doing the right thing for the right reason. There is no other incentive necessary."]

Dear Mr. ___: ... I agree with you that no incentive other than doing the right thing

for the right reason should be necessary.

However, at this time 66,717 people are on organ-donor waiting lists,

praying for a heart, a kidney or a liver that will save their lives. Last year,

4,800 people died while waiting for that prayer to be answered. Is it

more immoral for someone to die because there is a shortage of organs available, or to

offer tax incentives to those who would otherwise bury their dear departed, organs and

all?

I found this on Dear Abby's web site (2/8/00)

DONOR'S MOTHER FINDS HOPE IN LINKING LIVING WITH DYING

DEAR ABBY: In 1989, my nephew Bryan and his fiancee were killed in an automobile accident.

He was only 21 years old. My brother-in-law and sister were faced with that dreaded

question, "Is your son an organ donor?" In fact, he was, and had discussed his

wishes with his parents some time before the accident. As a result of Bryan's

unselfishness, several people's pain was ended and their bodies were mended.

A couple of years later, my sister was asked by a nurse who worked in transplant services

to speak to a group of medical professionals who deal with organ donation and donor

families. She was told that they never had a problem getting a recipient to come and tell

the story from that point of view, but it was rare to find a donor mom or dad who would

discuss how being approached for donation had affected their lives and what it meant to

them.

Those people wanted to know how she felt about what took place in that drab little room

off to the side of the emergency room on the night her son died. They knew they would be

faced with asking that question again and again, and wanted to know if she could give them

a word of encouragement or correction to make them better equipped to help the next

family. How could she refuse?

In the days to follow she wrestled with the thought of standing in front of a group of

strangers and pouring out the horrible story. She decided she needed to jot down something

that could be read for her in case she fell apart. In the space of an hour, the enclosed

poem is what God's grace allowed her to express. Perhaps you will feel it's worth sharing

with your readers. -- RON BELSHE, RICHARDSON, TEXAS

DEAR RON: I offer my condolences for the tragedy that took your nephew and his fiancee.

Your sister's poem is certainly worthy of space in this column. Read on:

DON'T GIVE UP

by Becky Hanson

If you can swallow hard enough to push away the fear,

And say yes to the question that no one wants to hear,

Then you will add a ray of hope when there's nothing left but crying,

And become the "gentle link" between the living and the dying.

I believe that you'll find comfort though your heart has been laid raw,

In offering hope to someone else who prays and waits in awe.

Until it's done, you can't know how or whom your words will bless,

But hundreds more will find new life if you will answer "yes."

By Bruce Japsen (Chicago Tribune staff reporter)

June 19, 2002

With 16 people dying every day for lack of a needed organ, the American Medical Association on Tuesday said it would support studies to determine whether money should be used to motivate potential donors and their families.

Although the AMA's decision is only a baby step toward financial payments for organ donation, the vote by the nation's largest doctor group is nevertheless significant, organ banks said. Just six months ago, the AMA's policymaking House of Delegates turned down a similar measure at its winter meeting in San Francisco.

This time, however, supporters of the measure were able to convince enough AMA delegates that the lack of available organs is, indeed, a crisis, and merely studying financial incentives could at least help medical professionals and lawmakers understand what drives donations.

Congress banned such financial incentives in 1984, leaving patients who need organ transplants to a volunteer system the AMA and other medical professionals admit has failed.

Nearly 6,000 Americans--an average of 16 a day--die each year as the waiting list for organs surpasses 75,000, a fivefold increase from the late 1980s.

"In a perfect world, altruism would be the answer, but we are not in a perfect world and all of the things we have tried to do haven't worked," said delegate Dr. Phil Berry, a Dallas orthopedic surgeon who had a liver transplant in 1986.

Berry said he was one of the lucky ones, receiving a liver donated from a woman who had died of a bleeding aneurysm. Berry had contracted hepatitis B from a patient during a 1983 surgery just four months before a vaccine became available for the disease.

"I feel so sorry for the 6,000 people who die every year and we need to look into anything that might help them," Berry said. The studies would only look at payments to the families or estates of patients who are dying. AMA policy forbids financial incentives paid to living donors.

Although the AMA itself wouldn't conduct pilot studies, the organization said it would help guide them so they meet ethical and scientific standards. The AMA said such studies, which don't exist, should be done by organ procurement agencies and transplant centers.

"The AMA is not endorsing the use of financial incentives to increase organ donation; it is simply recommending that this concept be studied," said Dr. Frank Riddick, chairman of the AMA's Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. "Financial incentives should be of modest value."

Among the incentives the AMA debated included tax credits or payments of $500 to $1,000 toward funeral expenses incurred by the donor family. A bill in Congress looking at ways to increase organ donation would provide a tax credit of up to $10,000 to the estate of an organ donor.

But opponents of incentives say paying donors is unethical and could dilute the altruistic motivation of donors.

"Financial incentives have the potential to exploit poor people," said Dr. Michelle Petersen, an Omaha physician from the eight-member Nebraska delegation, which opposed the effort backed by the AMA on Tuesday. "This promotes [selling] of the human body, reducing all of us as parts for sale. This is not ethical."

Doctors say most organ donations today are made at the last minute by families of people who have died unexpectedly. In such instances, many families decline to sign off on a donation.

Organ banks say the AMA's move will at the very least increase attention to the organ donation crisis.

The non-profit Regional Organ Bank of Illinois said it welcomed the AMA's support of the study.

"If this is going to increase organ donation, then it is something we would support," said John Valencia, the organization's spokesman.

"We don't know whether a study is going to be a positive or a negative," Valencia said. "The fact that this has been publicized may motivate people to donate."

Copyright © 2002, Chicago Tribune

Russell Korobkin's Oct. 30, 2005 Los Angeles Times Commentary

"Sell an organ, save a life

Compensation for donations? It's one way to help those on transplant waiting lists.

"

RUSSELL KOROBKIN is a UCLA law professor and a faculty associate at the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research.

ACCORDING TO RECENT reports, doctors at St. Vincent Medical Center in Los Angeles improperly transplanted a liver into a patient who was not at the top of the applicable waiting list. One person died who should have received the liver and didn't; one person lived by jumping the queue and receiving a liver to which he was not entitled. This is a scandal, but a small one. The far larger scandal is that thousands die every year waiting for transplants in this country because of a misguided government policy.

Nearly 90,000 people are on waiting lists for organs in the United States, most hoping for a kidney or a liver, fewer in need of a heart or a lung or a pancreas. Time runs out for about 6,500 each year.

Only a small percentage of deaths occur in ways that yield organs useful for transplants. Even so, if all those organs were harvested, there would be enough to provide transplants for most of those who die waiting. One important reason for the shortfall is that federal law prohibits donors or their families from receiving any compensation for donations.

The law — the National Organ Transplant Act — is based on the perfectly pleasant idea that organ donations should be altruistic. Unfortunately, the reality is that most of us are not very altruistic. Only a minority of Americans put the tiny "donor" sticker on driver's licenses or otherwise sign up to allow organs to be harvested and transplanted. Absent such prior assent, doctors are often reluctant to ask permission from the next of kin, and, when they do, the next of kin often refuse.

Some who choose not to be donors have a deep personal objection, religious or otherwise, to organ donation. Most people, however, fail to provide assent to donate because they don't want to confront their mortality. And why should they, when there is nothing in it for them or their families? It is much easier just to ignore the issue.

Surely the shortage of organs for transplant could be alleviated if the law were changed to allow modest payments for harvestable organs of the deceased. A system for providing incentives could be organized in many different ways.

The government could give a small tax break, perhaps $20 off driver's license renewal fees, to anyone who agrees to have organs harvested after death. The amount would be small because the organs may not be suitable for transplant. Alternatively, once a person has died, and doctors know that his organs are suitable, the next of kin could be paid a larger amount, perhaps a few thousand dollars, for the right to use those organs. The few who actually object to donating their organs can decline the inducements, while the many who have no strenuous objection will have an incentive to do the right thing.

Where would the money come from? The costs could be passed along to recipients, or more likely their insurance companies, Medicare or Medicaid. Transplant surgeries already cost tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars (hospitals, doctors and other transplant service providers are legally permitted to make money on organ transplants), so paying for organs and administering such programs would not increase the total cost of transplants appreciably.

Two common objections to permitting payment for organs are that the poor would be disproportionately likely to sell their organs and then suffer ill health effects, and that the rich, who could best afford to pay for organs, would disproportionately benefit. But both of these pitfalls are easily avoided.

First, compensation should be permitted only for organs of the deceased. As long as the living are not paid for a kidney or a portion of a liver, there is no reason to fear a coercive organ market. In fact, such a policy could drastically reduce the number of Americans and other Westerners who, in desperate need of a transplant, travel to Third World countries where they can receive organs sold by living donors.

Second, organ procurement should remain separate from organ allocation. The government or transplant centers should act as the purchasing intermediary and continue to allocate harvested organs according to factors such as medical need, likelihood of a successful transplant and time spent on a waiting list.

Current law pays an unacceptably high price to indulge the moral intuition that human organs should not be bought and sold. The law should be more concerned with saving the lives of thousands who die needlessly.